Introduction

John Cameron Mitchell’s 2001 film became a cult classic soon after its theatrical release. The film tells the story of Hedwig, who has grown up in Berlin during the time when the Berlin wall was built and demolished. The existence and absence of the wall are presented as metaphors for all the binary oppositions that film represents. The characters who don’t belong to any specific identity are all represented as “in between.” The film abstracts itself from political sayings, lies and inflexible notions and creates a world that has no prejudice. In this context it explores questions about the origin of love, the existence of a human being and the meaning of life. It uses mythological references and different mythological systems to find an answer to these questions, thus allowing us to analyze the narrative and narration on a mythological level.

The narrative focuses on the quest to find your other half. That’s why, as in mythology, we can call this film an “internal quest” story. Hedwig looks for his other half and he believes that it is Tommy, but he is making this quest with envy and to take his vengeance from him. As the quest progresses, we are given an idea about the past and present of these characters. In this complex narrative we meet with mythological references and actually with a mythological collage. We have Zeus from Greek mythology, Jupiter from Rome, Osiris from Egypt, Thor from Scandinavia and an Indian god who can knit. The heart of the film can be seen in the “Origin of Love” sequence, which summarizes the main theme. In this sequence the director (also the singer and narrator) brings forward the different mythological systems and tries to create a meaning for the origin of love. On the other hand, Hedwig has been described as a character whose looks change morphologically; that’s why Hedwig is also a symbol for metamorphosis, one of the main tools that mythological stories use to describe their characters.

This paper will try to determine the mythological components of the film and also how the film interprets these components to create a new discourse.

Janus: The Creation of the “Unitary”

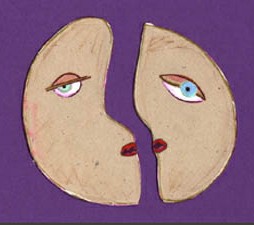

Hedwig’s main theme, “finding your other half,” is also presented visually many times. For instance, the sequence “Origin of Love” is just like a summary of this quest. On the other hand, the image of “Janus” is introduced to us for the first time but totally in a new shape. At the end of the film we also see the same shape on the naked body of Hedwig. This figure, the Roman god Janus, becomes a symbol for binary oppositions described in Hedwig. In film we always meet with the conflicts between present and past, male and female, war and peace, good and evil…etc. A new interpretation of these topics becomes visible with the structure of the film and the shape of the Janus symbol. Janus is presented not as a two-faced figure which looks at opposite sides; instead both sides of the figure integrate with each other and become inseparable. With that image all the oppositions in the film are symbolized as something that cannot be separated. They are all within each other, like Hedwig himself.

Like all the characters, Hedwig is someone who is in between. He is stuck between male and female bodies. After his sex-change operation he hasn’t become a 100% woman because an inch of his penis is still there. Yitzhak is another good example of this “in between” stiuation. His only dream is to become a drag queen like Hedwig, but (s)he has the physical appearance of a male. In the end (s)he turns into Venus and becomes a goddess. In this context, even though Hedwig is described as a drag queen, from a certain point through the end of the film this “stereotyped” notion has been deconstructed and Hedwig becomes someone who cannot be described by his physical appearance.

Hedwig is a character who’s looking for his other half but at the same time he doesn’t really know which half he belongs to. Hedwig is also between east and west; because he was born in Berlin, that also symbolizes the cultural and social “in between” situation of the character. Narrative makes this “in between” situation the main conflict of the film. All the characters and stories are integrated and engaged with each other in some way. Differences and similarities become something inseparable. As in many mythological stories, Hedwig and the Angry Inch emphasizes the inseparability of opposite notions and celebrates their unity. The main discourse of the film claims that ideas may exist only if they have their opposite side.

“The meeting of the oppositions” stiuation which was created with the help of characters and stories is also supported by the film’s structure. The linear narrative is always being interrupted with flashbacks, animated and non-diegetic inserts, which destroy the conventions of classical narration. The film’s musical structure also functions as an alternative to reality. In this context the film visually emphasizes the oppositions by breaking the borders between past-present, reality-dream (animated scenes), fictional-documentary. Thus the visual structure of the film mirrors the main theme of the narrative.

Both narrative and narration’s construction of these “oppositions” have also been discussed by the director himself. He talks about a specific group of people in Native American culture who are called “berdache” (twin spirits). They are neither male nor female and, like Shamans, are responsible for treating people and for religious ceremonies. The morphological situation of Hedwig after the unsuccessful sex-change operation mirrors the “berdache” personality of the protagonist.

The existence of two different sexes in Hedwig’s body references “androgynous” gods. They can be found in various mythological systems. This theologic notion comes out of the philosophical system of Gnostic Christians. The song “Origin of Love” in the film fully interprets this notion. In the lyrics, the discourse is centered on the idea of belonging to different powers and systems in the universe as a human being, asserting that we are a collage of the universe and not directly related to only one power or god. As the director has said, the reason for Hedwig’s metamorphosis into a sacred creature is, he carries the structure of this belief system in his body. Hedwig comprises two different bodies in one and that’s why he is reborn at the end of the film with the most famous element of Christian iconography, a cross, on his forehead. The conjunction of the cross and two different bodies lifts the character to the position of a “messiah.”

At the end the Janus figure appears on Hedwig’s naked body, which was also referenced in the animated clip of “Origin of Love.” Hedwig’s special relationship with past and present (and also the film’s itself) has been shown with Janus. It is no coincidence that we see the figure after the rebirth scene, because he was born as a new person but still carries the burden of the past on his body. It becomes the only “costume” he has and reminds us that we can’t erase the traces of the past.

Hedwig: Sustainability of Metamorphosis

Inclusion of characters who change their morphology is a sign for us that the notion of metamorphosis has a major role in the film’s narrative. The most obvious metamorphosis is Hedwig’s sex-change operation. We see Hedwig in a close-up before the operation; then a fade to white connects this image to the new “Hedwig” who carries a yellow wig. By this self-conscious transition the first metamorphosis in the film becomes visible. If fade to black means death in film grammar, fade to white becomes the signifier of life. If there is a metamorphosis then it should be admitted that there is also rebirth. Rebirth becomes visible with the language of film and fade to white becomes the rebirth moment of Hedwig. The film also brings a new interpretation of Hedwig’s metamorphosis. We see little Hansel (Hedwig) listening to rock music in the oven; in intercutting we see adult Hedwig also singing in the oven. But this time the camera turns around itself. Here the director uses an unconventional camera movement and a narrational repetition that compares the character with his past and present, and metamorphosis is emphasized again with the rolling camera. This indicates to us that metamorphosis is something sustainable and circular.

When Hedwig meets with Tommy at the end of the film, they look like each other, with the same clothes and cross figure on their foreheads. Literally they each meet with their reflection, their other half. This scene recalls the story of Narcissus, who falls in love with the reflection of himself on the surface of the water and faints from looking at himself and becomes a daffodil. But at the end, after Hedwig meets with his other half, they don’t get together and become “one.” We see Hedwig walking naked on the street. This scene tells us that the moment of finding your other half is the end of the journey and is no different from death. Because the quest ends. If you take life as a quest, every obstacle we have to overcome becomes a moment of rebirth for us. It is the same for Hedwig: that’s why we see him naked, as someone reborn.

Hedwig also shares some characteristics with Sif in Norse mythology. Sif is referenced in the “Origin of Love” scene as the wife of Thor; she has long blond hair and symbolizes fertility. In the original story, stone-hearted god Loki cuts Sif’s hair because she refuses to sleep with him. Thor feels sorry for his wife and he has a new wig made for her out of gold. The first similarity between Sif and Hedwig lies here; they both carry golden wigs. In another story, Sif turns herself into a tree to protect her husband and Thor hides in the tree. Thus Sif is a metamorphosed character like Hedwig. But Sif is a goddess who believes in monogamy. Hedwig is also someone who’s looking for his other half during his/her journey in the film. S(he) becomes the protector of Tommy and makes him what he is. However, there is a big difference between Sif and Hedwig. Hedwig may be looking for his other half and “the one” but he doesn’t believe in monogamy. When he meets with Tommy at the end of the film, he knows that he’s found his other half, but Hedwig lets Tommy go and doesn’t sacrifice himself for him and doesn’t become a “tree.”

In psychoanalytic terms, the relationship of Tommy and Hedwig reflects Oedipus’ story at certain points. They have a mother-son relationship after they first meet. Hedwig teaches him how to sing, takes care of him and makes love with him. As Freud said, an individual finds his/her self when he/she severs from the mother. Tommy finds his “self” when he severs from Hedwig, like Hedwig did himself. After the sex-change operation Hedwig took his mother’s name and left the country and his mother, thus finding his “self.” Similarly, Hedwig lets Tommy go and leaves him to stand alone in life. To sum up, the narrative rejects self-sacrifice or the urge to dedicate yourself to someone else. It asserts that we should find a new way in life when the time is right and leave the past behind, but without forgetting it, as the Janus tattoo represents Hedwig’s past on his naked body.

Conclusion

The variety of mythological systems in Hedwig also reflects the film’s thesis on variety in society. Characters are not presented in accepted terms like male/female, good/bad, American/German…etc. Uncertainty and ambiguity of the characters’ physical properties make all of them anti-heroes. They are easily unconventional characters who are in between on everything. You can’t find any tags for these characters because they don’t fit any preconceived notion. The film celebrates variety and censures discrimination. Bisexuals, gays, lesbians, transsexuals and transvestites who are described as “unusual” by society become ordinary and usual for the audience. Because it is totally their story. This also corresponds to mythology’s interpretation of the human condition. In mythology ordinary becomes extraordinary or extraordinary becomes ordinary. Hedwig and the Angry Inch does the same thing for its characters. Personalities who are described as extraordinary, unusual, uncommon, out of society, become common and ordinary. By doing this the film celebrates the human being as something beautiful and important in itself and breaks the labelling mechanism in our heads.

References

İnsan ve Sembolleri, Carl Gustav Jung, Okuyan Us Yayınları, December 2007

Sinema Modern Mitoloji, Ömer Tecimer, Plan Yayınları, July 2005

Narration in Fiction Film, David Bordwell, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1985

http://www.novareinna.com/festive/janus.html