“There comes a point when a dream becomes reality and reality becomes a dream.”

Frances Farmer

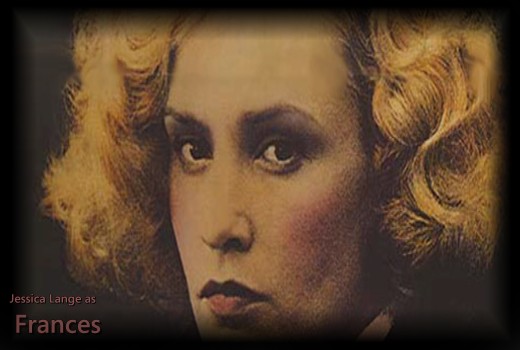

Through many years of careful analyzing of the facts, I have come to realize that had I not seen the film poster in question, my life would be completely different now. The (eventual) sheer profundity of such a seemingly innocent moment, where a young boy shares a formative glance with a movie star (in this case actress Jessica Lange playing actress Frances Farmer), never ceases to surprise me. Had I not been wandering aimlessly around the halls of Winchester Mall’s sad-sack movie theater in Rochester Hills, my seven-year-old mind racing after another viewing of The Empire Strikes Back, I might not have come to a complete stop in front of the most arresting image I had ever seen. The film art for Frances took my breath away and to this day, when I see it, I am taken back to that exact moment, feeling so small staring up at this larger-than-life, troubled goddess of classic cinema. I would repeatedly go back to the theater’s concourse just to watch this woman, half-dazed, trying to understand why she looked so sad.

What first caught my attention was the haunted look in Lange’s eyes – stone black, fearful, yet willful. The “look” is similar to what hooks notes in her essay, discussing her father’s photo and his possession of “such boldness, such fierce openness in the way he faces the camera” (54). For me, Lange’s portrait immortalized on this one-sheet encapsulated the qualities that I hoped to one day possess: strength, confidence, even the courage to speak up for myself loudly and declare my own artistic freedom and uniqueness in an oppressing environment. The soft roses and gray-lilac tones that framed a nimbus of 1930s platinum blonde hair recalled a time that I needed to know more about, and in fact sparked my lifelong interest in the role of women in film. But in this image there was also a darker flip side to the classic Hollywood glamour and wild streak, a tragic reality that most gay men I know tend to naturally gravitate towards. Farmer, though immensely talented, was also a tormented, tragic figure who would gain notoriety first in her life as a teenager when she denounced God and went to Communist Russia to study theater. Consistent stage work brought her to the attention of the major studios who quickly saddled her with an oppressive contract that did not allow for her natural razor-sharp instincts and wit to be properly utilized. Because women were not encouraged to share their opinion in Hollywood at the time, Farmer was labeled “difficult” and spent the rest of her life in a hell of booze, pills, and primitive mental institutions; she was finally lobotomized for her outspokenness at the behest of her mother (Frances). All of this rich, troubling history was accounted for in Lange’s look on the poster and it was as though she was asking for my help, begging me to see the film, to hear her story. Was it Farmer asking this of me or was it Lange? When I first saw this image, I had no idea who Farmer was nor did I have the first clue about the details of Lange’s own tumultuous personal journey to playing the character. But as a seven-year-old Barbie enthusiast in a time when my contemporaries were firmly implanted into the lands of GI Joe and He-Man, I was already no stranger to bullying, obstacles and even glamour. I knew I had to see this movie and figure out this strange attraction.

If every face tells a story, the poster art for Frances was telling two that paralleled a feeling that I would come to know too well, in my real life over the years. Both women’s backgrounds felt wildly similar to my own struggle to maintain identity in the face of adversity, oppression and even occasional violence. I could identify with someone struggling with not fitting in and being unfairly punished for it despite misguided, loud-mouthed attempts to counter the negativity. The first story told in the film was that of Farmer, a beleaguered, quasi-iconic artist trying to navigate a system that undermined the ideals she held dear and eventually destroyed her. The second was the triumph of a former model who up until this point had not been taken seriously by a single critic: Lange’s coming into her own as a performer, establishing an identity in film forever thanks to this role of a lifetime.

In retrospect, I can see why I would be absorbed into such a powerful image, at such a crucial time in my young life. Hooks writes that photographs “remain a mediation between the living and the dead” (hooks, 63), which made me think there could be a supernatural force at work here trying to teach me a lesson of some kind. That sentiment set off a veritable explosion in my head: I realized that the female icons of the Golden Era of cinema (and even to an extent current cinema) are as important to the coming of age of gay men as the photos hooks describes were to black culture’s desire to shape and control their own images after years of being caricatured. Both groups wanted to present the ultimate fantasy ideal of what they wanted to be. Just as hooks describes the suffering of African American people from the lack of positive photographic representation, I similarly had no positive images of gay men to look up to in 1982. There was Liberace. There were The Village People. There were images of lonely men dying in pain from a new “gay” disease called AIDS. There were hateful, hurtful stereotypes inundating the media of the time, but there was no truth. I much preferred to think of myself in a class with these strong, talented, outspoken women than with a guy dressed up in leather chaps. What held true for images of homosexuality at that point in American history was much like hooks observing that “degrading images of blackness that emerged from racist white imagination were circulated widely in the dominant culture” (59).

The images I saw of gay men in these years frightened me, but the polished, sophisticated pictures that countered these, at least in my young mind, were of these untouchable icons of film. Frances Farmer, Jessica Lange, Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Gena Rowlands and many others represented what I wanted to become. They all represented what every gay man wants to be: adored by many, beautiful, successful, and gifted; but these icons can also be used, in most cases, as a cautionary tale of what not to do. These women, through their work, their images and their private lives, function as powerful tools of reflection, mirroring both history and our inner selves, but also shining a bit of light on the future if one looks close enough to learn how to properly wield influence and assertiveness, how to filter the thoughts that are in our heads so our mouths don’t just allow them to escape at inopportune moments and get our bodies into physical trouble. Hooks says that the formative image of her as a girl in a Western Halloween costume gave her a sense of “presence, girlhood beauty and capacity for pleasure” and enabled her to become “all that I wanted in my imagination” (hooks, 56), and I felt something similar lost in the gaze of these movie stars, but particularly Lange on the Frances poster. “Using images, we connect ourselves to a recuperative, redemptive memory that enables us to construct radical identities, images of ourselves that transcend the limits of the colonizing eye,” hooks says in the final paragraph of her piece as she reflects on the power of the photo to act as a primal force in the life of minorities to reclaim and reconstruct their images in spite of their oppressors (hooks, 64). In my case, power, glamour and talent were the world I wished to explore, I wanted to make it my reality, and I didn’t want to be consigned to a world of stereotypical gay images propagated by an unkind popular culture. I wanted to be a part of the film world, the world of Frances Farmer, the world of Jessica Lange, the world of actresses.

This image of Lange as Frances perfectly summed up complicated feelings of being lost or searching for something in me in many ways, and nearly thirty years later, though my understanding of the artwork has changed, its content remains firmly implanted in my consciousness, seeps into my academic and professional work, and has inadvertently changed the course of my life. There was a secret hidden in Farmer, a coded message of how to live one’s life without fear of authority or reprisal, and without sacrificing whatever wildness or charisma might live inside the tumultuous mind of a young gay man who thought those were bad qualities. This secret was being delivered through a contemporary medium channeling this “wild” essence for a new generation to learn from. Through this image I have been able to learn to confront my own problems head-on, to explore dark, obscure corners of film history and to take a close look at the role of women and feminism in film, an interest that has thrust me into such bizarre, previously unimaginable scenarios as hanging out in a hotel room in New York with legendary British film director Mike Leigh, cultivating a meaningful professional relationship with another idol (composer Tori Amos) , and chatting casually with Iranian expatriate actress Shohreh Aghdashloo about the rights of women in Muslim countries.

Frances so haunted me that even into my adulthood and professional career as a film columnist I was still intently covering the work of Lange. Two fateful years ago I came to New York to see Lange, my childhood hero, give a talk at the 92nd Street Y, which was moderated by Dr. Annette Insdorf, the head of Columbia University’s film department, in yet another women-from-the-film-world twist of fate. Had I not been so drawn into the black web of Lange’s eyes on that poster at such an early age, so transfixed by the power behind the gaze, I probably never even would have been in the city in the first place, let alone sitting captive in an audience with Lange holding court. This time, though, I was “transfixed” by yet another fascinating woman, Insdorf, a world-renowned film scholar and authority on the subjects I felt so connected to, which led me to apply to the school that this whip-smart, fascinating person taught at. The image of Lange as Farmer was powerful in forming my interest in film in the first place, but also would emerge as a key element that actually shaped my future as a professional in the film industry and, eventually, as a film scholar at Columbia, much like hooks’ photos of herself as a cowgirl and the snapshot of her father shaped her destiny as a historian, author and scholar. It all started, improbably, with just one look and a picture. My life changed forever in that all-consuming moment thanks to being inspired by a simple photograph. The experience continues to evolve for me, as hooks’ thoughts on her treasured photos do for her, taking on a greater significance as the years go on and I reflect on where I might have ended up without the influence of this image.

Works Cited

hooks, bell. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life”. Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press. 54-64. 1995.

Frances. Dir. Graeme Clifford. Perf. Jessica Lange, Kim Stanley, Sam Shepard. Universal, 1982. Film.

“Frances Farmer Quotes”. BrainyQuote. 28 Sept. 2009. <brainyquote>.