Comolli and Narboni asserted that “every film is political” (689), and Denis’ is a work that can be peeled back onion-like, layer by layer, to reveal a stinking message perhaps not caught by a typical heterosexual spectator. Galoup has visions of heaven that feature firm young men in uniforms looking beautiful and smiling at him, and is drawn as the most evil character in Denis’ film; Sentain, on the other hand, incarnates good. Because it is implied that Galoup has homosexual tendencies or desires that he represses, and because she then chooses for him to end his own life by the end of the film, Denis’ motivations underlying the formal construction of her film must be interrogated.

Comolli and Narboni also said that “cinema is one of the languages through which the world communicates itself to itself” (689). So what is Denis trying to communicate to her audience by choosing to end her film with the final suicide? The white, heterosexual female director makes a strong filmic comment by inferring that the only way for this character to resolve his turbulent mind, addled by homoerotic thoughts, is to kill himself. I argue that this surprising scene, while in some ways recapitulating hegemonic notions of repressed homosexual suffering, reflects back upon the formal system of the film itself. The images of sexual gaze and longing which ostensibly saturate the film obfuscate a trenchant critique of colonial practice and domination. Unfortunately, this critique, while hardly submerged in the film, becomes itself repressed by a hegemonically heterosexist gaze which lingers only on the questions of sexuality, leaving the racial and political tensions of the film uninvestigated.

Beau Travail does challenge a prevailing white, heterosexual male Hollywood gaze and conditionally attacks a particular political ideology. When it comes to how the indigenous people are portrayed in the film, Denis reveals herself as a sympathetic, humanist filmmaker who understands the need for the locals to use their own language and their own traditions if the film is to feel authentic and challenge the conventional gaze of the colonized. Stam and Spence define the colonized as those affected by ”the process by which the European powers (including the United States) reached a position of economic, military, political and cultural domination in much of Asia, Africa and Latin America” (Stam and Spence 753). In Beau Travail Denis shows the African people as warm and caustic, both modern and reverent to tradition. It is a balanced, empathetic gaze, likely realized because of the director’s own upbringing in West Africa.

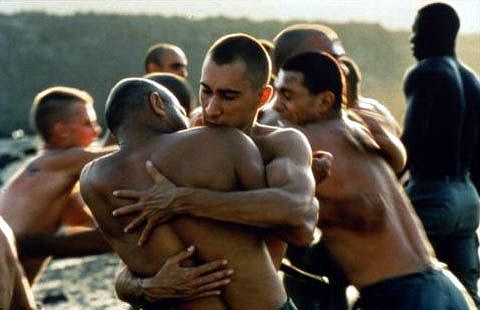

Denis gives the indigenous people their own voice, showing what their daily activities are like, capturing their native language in use so as to avoid the “absence” that Stam and Spence think often ends up “reduced to an incomprehensible jumble of background murmurs” (Stam and Spence 756). The scene in which the women discuss the stripes on fabric is a wonderful example of how Denis chooses to portray the minutiae of the country with loving detail by depicting the everyday, seemingly innocuous interactions of the colonized and juxtaposing that bit of color with the gaudy western logos of the Coca-Cola Corporation. This extreme contrasting of nature with modernity is also suggested more abstractly through Denis’ choices to juxtapose images with strong homosexual connotations to images of war and soldiers, so that she is perhaps damning the idea of war or traditional masculinity’s place in war. Showing the group of men doing their rigorous training, letting the camera virtually caress their glistening, muscular bodies and their glances that are held for just a second too long lends an illusion of, if not a homosexual gaze, at least a gay-friendly one.

Sadly, despite trying to dismantle the traditional male gaze, Denis forgets to counter or anticipate what Stam and Spence refer to as “hegemonic images” (Stam and Spence 757) of gay culture. The director’s emphasis on the homoerotic nature of the characters and on the images themselves lends to the work becoming overly fetishized, thereby turning the characters and images into objects of fascination. Extending Stam and Spence’s insights, we might call these queer groupings of themes and sensual imagery “the colonized” oppressed by their heterosexual audience and by their heterosexual maker. Denis does lovingly display the bodies of the men, attempting to turn them into objects of erotic desire, but the effect for the viewer is instead to coalesce the images into simple curiosities for heterosexual spectators who are by and large very uncomfortable when confronted with the depiction of two men touching each other in any way that could be construed as sexual, even when it is only implied. Homosexuality and homoeroticism becomes the key “other” in Denis’ film, despite the clear attempts to foreground the colonial relationship. The director’s point of view could be read then as a reinforcing heterosexist gaze that colonizes in its own way despite what might be the director’s best intentions to make a film that satisfies what Comolli and Narboni refer to as “content [that] is not explicitly political, but in some way becomes so through the criticism practiced on it through its form” (Comolli and Narboni 690).

As a gay spectator viewing Beau Travail in a room of mainly heterosexual viewers, it was painful for me to witness just how the mere suggestion of gay sexuality was enough to send people into veritable fits of uncomfortable paranoia for reasons they could not articulate. Though Denis cleverly constructs her film to only imply sexuality, and though the legionnaires are clearly heterosexual (as evidenced by their interactions with local women at the club), when men touch each other’s bodies on film, the audience’s perception and comfort zones are toyed with. Homosexuality, or the implication of it, becomes the focal point for the viewer, doing a disservice to Denis’ broader political intentions. The director has thus created an anti-Colonialist piece of visual poetry that is much more dense than critics give it credit for as they become preoccupied by the implicit gayness of the work, entangled in a knotty web of confusing and implied sexuality, crippling their understanding of the film. Rather than reading the scene where the legionnaires go through maneuvers and roughly “embrace” one another in simulated hand to hand combat as being a beautiful expression of camaraderie and strong work ethic triumphing over loneliness, the straight spectators impute them as being homoerotic, simply because the scene involved men, without shirts, touching one another’s flesh in an up close and personal way. Beau Travail is unfairly read as a film that is simply and only homoerotic, rather than as the assault on conventional cinema and the tropes of colonial representation that it actually is.

In the final scene of Beau Travail, as Galoup lies on his meticulously made cot, pulse racing as images of beautiful young soldiers float through his head, the promise of being reunited with them driving his actions, the spectator must question Denis’ intention by choosing to have the character kill himself in order to connect this final scene to the film’s formal system. Throughout the film, the director has shown Galoup as an aged stalker, as someone who is desperately trying to fit into this young, gorgeous group of men but is more of a loner, a square peg. He carefully controls his own image, ironing perfect creases in his shirts, combing his hair just so and shaving his face closely. The preening Galoup is shown gazing at his own image in mirrors throughout the film, which, combined with his following of and fantasizing about the soldiers, indicates that he might be driven by vanity. As he smartens up in the mirror about thirty minutes into the film, combing his hair, and looking very pleased with what he sees, Denis follows the scene with an image of blood exploding in orange clouds against the green sea as the helicopter crashes into the water, foreshadowing that male vanity equals death. Galoup’s suicide, it could be concluded, was motivated by his unconscious hatred of these beautiful young men, a hatred which amounts to Galoup’s own self-hatred.

By choosing to conclude the film this way, Denis makes a bold statement on repressed homosexuality. When Galoup finally pulls the trigger (off-screen), the viewer is left asking: is the director propagating a homophobic, heterosexist notion that repressed homosexual longing is a reason for a straight man to kill himself? Is having loving thoughts about other men the ultimate taboo for straight men, after which there is no “way out” other than to kill oneself? Is the only way for a tortured man like Galoup (who Denis wants the audience to see as genuinely loving his compatriots) to find true peace and happiness to take his own life? Denis raises many questions with her final scene, rather than giving the spectator a pat conclusion in which answers are clear (in Billy Budd, Claggart is accidentally killed by Billy). Galoup’s chest tattoo reads, “serve the good cause and die.” Does this mean serve the “straight” cause and die if you don’t fit into the ideals of traditional masculinity?

Perhaps, in the end, this is the ideology Denis intends to attack with Beau Travail: the mistaken equation of hyperphysical masculinity and heterosexuality. In suggestion, though, Denis’ film becomes less of a revolutionary, artful act and more of what Comolli and Narboni refer to as a film that espouses the public’s fascination with films depicting “what the dominant ideology wants” (689). We expect this kind of extreme machismo from big-budget Hollywood fare that is focus-grouped to death and created by committee, but not from French art-house cinema, which is supposed to be immune to these staid rules.

Corona’s “The Rhythm of the Night,” a tacky gay anthem, pulsating against tracks of red blinking lights and a mirrored wall, is Denis’ idea of a gay heaven’s soundtrack. She inserts Galoup into her straight fantasy, forcing him to find happiness in a gay bar, alone. The soft lights and smokiness mask Galoup’s face in a way that, combined with his exultant movement, makes him into an ageless phantom. The character spastically churns with the beat of the song, moving in a freed way that his prim and proper character had not been allowed to express before. The scene might easily be seen as a release by the straight and/or casual viewer, as though Galoup is exorcising his demons and no longer a tortured soul, as though he is finally at peace after shooting himself. He is set free to move, to be young again, shown through his expressive body language, complete with limp wrists and hands positioned on hips in a fey manner – loose movements he never would have contemplated while alive – as he builds up to a frenzied crescendo of dance moves.

It could be read by a queer spectator, though, that rather than a “gay heaven” for Galoup, Denis has chosen to put him firmly inside a gay hell. The final scene of Beau Travail could be seen as the character’s everlasting punishment for killing himself: an eternal afterlife spent alone dancing against the shimmering red lights, forced to confront his own hated image in the mirrored wall. While the red track lights and the mirrored wall are intrinsic to Beau Travail’s earlier scenes that reinforce heterosexual normalcy, the film departs in style at the end because Galoup is now alone in a straight woman’s idea of what the gay afterlife is: pulse-pounding club music, an ever-present cigarette, lights, vanity mirrors and dancing.

This is, itself, a stereotype, and in not addressing the implications of the film’s final scenes in a more direct or solid manner, Denis’ film fails in attacking the prevailing macho Hollywood gaze, which dictates that queer characters are innately abhorrent in some way and that they must die for their transgressive desires. For straight audiences, the ending of Beau Travail is Galoup’s pitiable triumph, but to a gay audience there is a danger of his suicide being read as something more deeply troubling: the ultimate act of contrition for simply having queer desires in a heterosexual world. Is death Galoup’s way of gaining control over his life, or is it simply his way of fitting into a heterosexually ordered, myopic view of sexuality? Denis leaves it up to her audience, but that directorial choice abandons the maverick spirit that is present throughout the entire film until the final scene, that toys with audience perception, actively subverting traditional techniques of representing colonized peoples. Indeed, the ending feels rushed, like a run through an unexplored terrain, when compared to Denis’ meditative look at the images of the landscapes, the men, and the Djiboutian culture. With this one single act, the potential for a truly revolutionary statement – and a coherent formal structure which reflects a coherent sociopolitical commentary – is squandered, leaving the audience feeling as though heaven is a lonely gay bar with bad music.

Works Cited

Comolli, Jean-Luc, and Jean Narboni. “Cinema/Ideology/Criticism.” 1968. Film Theory & Criticism. 7th ed. New York/London: Oxford UP, 2009. 686-93. Print.

Stam, Robert, and Spence, Louise. “Colonialism, Racism, and Representation: An Introduction.” Film Theory & Criticism. 7th ed. New York/London: Oxford UP, 2009. 751-56.