One Battle After Another and The Secret Agent Lead ICS Nominations

Honoring films shown worldwide in 2025.

A pair of well-timed thrillers about the cruel persecution of refugees scored the most noms with ICS voters this year. Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, with 12 mentions, turns a satirical gaze on US immigration policy over the past two decades, as a revolutionary group goes underground to protect its members from brutal repression by the military. Bob (Leonardo DiCaprio) and his daughter Willa (Chase Infiniti) have been living under fake identities ever since Willa’s machine-gun wielding mother Perfidia (a ferociously entertaining Teyana Taylor) decamped to Mexico. But things heat up fast when teenage Willa is kidnapped and Bob goes on a drug-addled crusade to rescue her, only to find that his resourceful kid can take care of herself. With outstanding ensemble acting and impeccable craftsmanship, Anderson points out the racist, immoral wasteland that the United States of America has become.

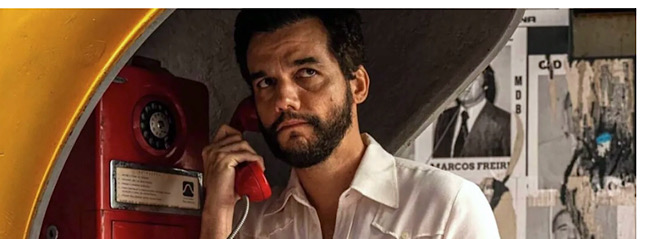

Brazilian auteur Kleber Mendonça Filho revisits life under the military dictatorship of 1977 in The Secret Agent, which earned 10 ICS nominations. It’s a warm, colorful look at refugees hiding from political retribution in Recife (the director’s hometown), beset by carnival madness and a carelessly corrupt police force. This unorthodox and heartbreaking film shows a community of people in dire straits coming to trust each other under the protective wing of long-time resister Dona Sebastiana (Tânia Maria). The remarkable Wagner Moura gives a nuanced performance as Armando (aka Marcelo), forced to navigate hitmen, gas station corpses, hairy legs and sharks of every kind while trying to flee the country with his young son. On all fronts, from clever writing to ensemble acting to brilliant cinematography, Mendonça has created a masterful look at the human cost of fascism.

Other best director nominees included Dag Johan Haugerud for Dreams (Sex Love), the final installment of his Oslo Trilogy; Kelly Reichardt for The Mastermind, her quiet character study in the guise of an art heist; and Mascha Schilinski for Sound of Falling, a haunting story of four women who lived at various times in an isolated German farmhouse. Continuing with the father-daughter theme so prevalent this year, ICS also nominated Oliver Laxe for his existential pilgrimage across a perilous bridge to heaven called Sirāt; and Alexandre Koberidze for his moving, ethereal football odyssey Dry Leaf.

Winners of the 23rd ICS Awards will be announced on February 8, 2026.

PICTURE

• Dreams (Sex Love)

• Dry Leaf

• Hamnet

• I Only Rest in the Storm

• It Was Just an Accident

• Last Night I Conquered the City of Thebes

• Marty Supreme

• The Mastermind

• Mektoub, My Love: Canto Due

• Nouvelle Vague

• One Battle After Another

• Resurrection

• The Secret Agent

• Sentimental Value

• Sinners

• Sirāt

• Sound of Falling

• Strange River

• Twinless

• Weapons

DIRECTOR

• Paul Thomas Anderson – One Battle After Another

• Dag Johan Haugerud – Dreams (Sex Love)

• Alexandre Koberidze – Dry Leaf

• Oliver Laxe – Sirāt

• Kleber Mendonça Filho – The Secret Agent

• Kelly Reichardt – The Mastermind

• Mascha Schilinski – Sound of Falling

ACTOR

• Timothée Chalamet – Marty Supreme

• Sope Dirisu – My Father’s Shadow

• Ethan Hawke – Blue Moon

• Wagner Moura – The Secret Agent

• Dylan O’Brien – Twinless

• Ben Whishaw – Peter Hujar’s Day

ACTRESS

• Jessie Buckley – Hamnet

• Rose Byrne – If I Had Legs I’d Kick You

• Kathleen Chalfant – Familiar Touch

• Jennifer Lawrence – Die My Love

• Ella Øverbye – Dreams (Sex Love)

• Tessa Thompson – Hedda

SUPPORTING ACTOR

• Benicio del Toro – One Battle After Another

• Jonathan Guilherme – I Only Rest in the Storm

• Salim Kechiouche – Mektoub, My Love: Canto Due

• Sean Penn – One Battle After Another

• Alexander Skarsgård – Pillion

• Stellan Skarsgård – Sentimental Value

SUPPORTING ACTRESS

• Cleo Diára – I Only Rest in the Storm

• Nina Hoss – Hedda

• Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas – Sentimental Value

• Amy Madigan – Weapons

• Tânia Maria – The Secret Agent

• Teyana Taylor – One Battle After Another

ENSEMBLE

• I Only Rest in the Storm

• It Was Just an Accident

• Marty Supreme

• One Battle After Another

• The Secret Agent

• Sentimental Value

ORIGINAL SCREENPLAY

• Dreams (Sex Love) – Dag Johan Haugerud

• Marty Supreme – Josh Safdie, Ronald Bronstein

• The Secret Agent – Kleber Mendonça Filho

• Sentimental Value – Eskil Vogt, Joachim Trier

• Sorry, Baby – Eva Victor

• A Useful Ghost – Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke

ADAPTED SCREENPLAY

• Bugonia – Will Tracy

• Hamnet – Chloé Zhao, Maggie O’Farrell

• No Other Choice – Park Chan-wook, Lee Kyoung-mi, Don McKellar, Jahye Lee

• One Battle After Another – Paul Thomas Anderson

• Pillion – Harry Lighton

• Pin de Fartie – Luciana Acuña, Mariano Llinás, Alejo Moguillansky

CINEMATOGRAPHY

• Dry Leaf – Alexandre Koberidze

• Magellan – Lav Diaz, Artur Tort

• One Battle After Another – Michael Bauman

• Resurrection – Dong Jingsong

• The Secret Agent – Evgenia Alexandrova

• Sound of Falling – Fabian Gamper

EDITING

• A House of Dynamite – Kirk Baxter

• Marty Supreme – Ronald Bronstein, Josh Safdie

• One Battle After Another – Andy Jurgensen

• The Secret Agent – Matheus Farias, Eduardo Serrano

• Sirāt – Cristóbal Fernández

• Sound of Falling – Evelyn Rack, Billie Mind

PRODUCTION DESIGN

• Frankenstein – Tamara Deverell

• Marty Supreme – Jack Fisk

• The Phoenician Scheme – Adam Stockhausen

• Resurrection – Liu Qiang

• The Secret Agent – Thales Junqueira

• Sound of Falling – Cosima Vellenzer

SCORE

• Dry Leaf – Giorgi Koberidze

• Marty Supreme – Daniel Lopatin

• The Mastermind – Rob Mazurek

• One Battle After Another – Jonny Greenwood

• Resurrection – M83

• Sirāt – Kangding Ray

SOUND DESIGN

• Die My Love – Tim Burns, Paul Davies

• One Battle After Another – Christopher Scarabosio

• Reflection in a Dead Diamond – Daniel Bruylandt

• The Secret Agent – Tijn Hazen

• Sirāt – Laia Casanovas

• Sound of Falling – Billie Mind, Jürgen Schulz

ANIMATED FILM

• Arco – Ugo Bienvenu, Gilles Cazaux

• Boys Go to Jupiter – Julian Glander

• KPop Demon Hunters – Chris Appelhans, Maggie Kang

• Lesbian Space Princess – Emma Hough Hobbs, Leela Varghese

• Little Amélie or the Character of Rain – Liane-Cho Han, Maïlys Vallade

• Zootopia 2 – Jared Bush, Byron Howard

DOCUMENTARY

• Cover-Up – Mark Obenhaus, Laura Poitras

• Fiume o morte! – Igor Bezinovic

• Memory – Vladlena Sandu

• The Perfect Neighbor – Geeta Gandbhir

• Put Your Soul on Your Hand and Walk – Sepideh Farsi

• With Hasan in Gaza – Kamal Aljafari

DEBUT FILM

• Blue Heron – Sophy Romvari

• Familiar Touch – Sarah Friedland

• Last Night I Conquered the City of Thebes – Gabriel Azorín

• Sorry, Baby – Eva Victor

• Strange River – Jaume Claret Muxart

• A Useful Ghost – Ratchapoom Boonbunchachoke

BREAKTHROUGH PERFORMANCE

• Chase Infiniti – One Battle After Another

• Guillaume Marbeck – Nouvelle Vague

• Santiago Mateus – Last Night I Conquered the City of Thebes

• Jessica Pennington – Mektoub, My Love: Canto Due

• Ubeimar Rios – A Poet

• Eva Victor – Sorry, Baby