I felt I was caught in a film festival Möbius strip of Lynchian proportions or (failing that), at least a very strong sense of déjà vu. Half a year after it served as headquarters for TCM’s Classic Film Festival, I again found myself in the “Blossom Room” of Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel.

Site of the first Academy Awards banquet, this time the historic hall was the center of AFI Fest 2010 (presented by Audi, whose sponsorship allowed for free tickets to all screenings during the week-long festival). On the fest’s first full day, AFI treated members to a “Movies & Martinis” reception in the intimate room, and it was hard not to think how the film world has changed since that evening some eighty years ago when Douglas Fairbanks, Mary Pickford, Clara Bow and other silent screen legends congregated to distribute these odd new awards.

Speaking of Oscar, the AFI Fest has quickly morphed into one of the hometown springboards in the annual quest for a coveted Academy Award nomination. Immediately following the martini reception at the Roosevelt, potential nominees in this year’s derby were simultaneously pleading their respective cases in the dueling cinema palaces that Sid Grauman built. At the opulent Chinese Theatre, odds-on acting favorites Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush were discussing The King’s Speech with director Tom Hooper. A few blocks away at Grauman’s Egyptian, their likely competitors Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield from The Social Network were part of a Young Hollywood discussion panel, along with 2009 Actress nominee Carey Mulligan.

Andrew Garfield was in the privileged position of having recently worked with both of his co-panelists in his last two films, and seemed to be the most gregarious of the group. Charmingly self-deprecating, Garfield riffed on his meteoric career trajectory, admitting concern and bemusement over being cast as the next Spiderman, and the lack of anonymity that will no doubt follow. His loopy stream-of-consciousness rambling had the audience in stitches, and he and Eisenberg clearly enjoyed ribbing each other throughout the discussion. Both remarked on how, as actors, they wished they’d been able to meet their respective Social Network characters before the shoot, but admitted that their inability to do so allowed them (especially in Garfield’s case) to interpret Zuckerberg and Eduardo with much more artistic freedom. Surprisingly, Eisenberg mentioned that his cousin now actually works for Facebook, and that Mark Zuckerberg (after a private screening party for employees) let it be known that he thought Eisenberg’s portrayal of him was indeed a good one.

For her part, Carey Mulligan (exuding a real movie-star presence) spoke of how rapidly things have changed for her in Hollywood – from taking public buses around town just a few years ago, to walking the Oscar red carpet as a Best Actress nominee earlier this spring. Quietly confident and well-spoken, Mulligan touched on the great sadness she feels when one of her movie shoots nears its end. She’s particularly dreading the end of her current film Drive (her favorite so far), as she’s thoroughly enjoying her work with co-star Ryan Gosling. As for Gosling, he worked the Chinese red carpet the following night, drumming up support (and another possible nomination) for his performance opposite Michelle Williams in Blue Valentine. In fact, in a year when the Academy Awards race seems to be wide open, the AFI Fest offered many opportunities for hopeful nominees to showcase their work.

Anne Hathaway and Jake Gyllenhaal walked the red carpet for the festival’s Opening Night gala of Love and Other Drugs, while previous Oscar honorees Dustin Hoffman and Kevin Spacey attended the Hollywood premieres of their respective hopefuls, Barney’s Version and Casino Jack. Halle Berry took to the Chinese stage for a “Conversation on Acting,” with the exposure for her upcoming Frankie and Alice presumably just a side benefit. Mark Wahlberg spoke to the congregation before a “surprise” screening of David O. Russell’s The Fighter, and Darren Aronofsky introduced the stunning cast members of Black Swan (Winona Ryder, Barbara Hershey, Mila Kunis, and Actress frontrunner Natalie Portman) before that film’s Closing Night gala.

After another likely-to-be-nominated Actress showcase unspooled at the Egyptian, the unlikely-to-be-nominated men of Rabbit Hole took to the stage to discuss their film and field questions from the audience. Director John Cameron Mitchell was particularly humorous and eloquent, discreetly mentioning how a death in his own family prompted him to pursue the film rights for the Pulitzer-winning play.

After another likely-to-be-nominated Actress showcase unspooled at the Egyptian, the unlikely-to-be-nominated men of Rabbit Hole took to the stage to discuss their film and field questions from the audience. Director John Cameron Mitchell was particularly humorous and eloquent, discreetly mentioning how a death in his own family prompted him to pursue the film rights for the Pulitzer-winning play.

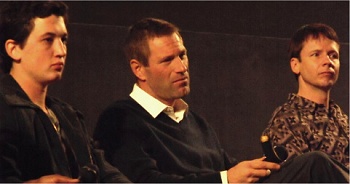

Quite the departure from his earlier, vastly more original work, Rabbit Hole was nevertheless a decent film, even if it dealt with perhaps that most baity of Oscar subjects – grieving parents coping with the death of a child. Thankfully the film’s histrionics were a bit less in your face than usual for this genre, and for me the top acting honors went to the truthful, interior performance of Miles Teller, who joined Mitchell and co-star Aaron Eckhart on stage.

Quite the departure from his earlier, vastly more original work, Rabbit Hole was nevertheless a decent film, even if it dealt with perhaps that most baity of Oscar subjects – grieving parents coping with the death of a child. Thankfully the film’s histrionics were a bit less in your face than usual for this genre, and for me the top acting honors went to the truthful, interior performance of Miles Teller, who joined Mitchell and co-star Aaron Eckhart on stage.

In addition to the annual jockeying for Academy attention, AFI Fest 2010 was an exciting platform for the finest of recent world cinema. Nearly twenty films that had premiered at Cannes earlier this spring made their Hollywood debuts, including beautifully mystifying Palme d’Or winner Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, as well as Abbas Kiarostami’s Certified Copy, a showcase for luminous Best Actress winner Juliette Binoche. While Kiarostami, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and recently Oscared(!) Jean-Luc Godard were not on hand to introduce their latest films, ever-brilliant Werner Herzog did appear to present Cave of Forgotten Dreams, his first film shot in 3-D.

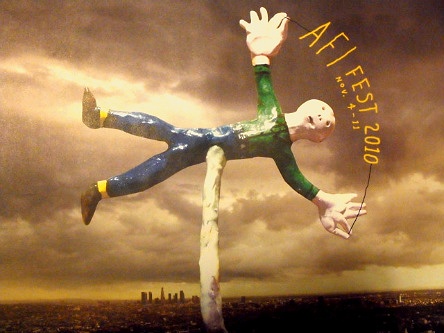

But foremost among the cinematic masters in attendance was undoubtedly Mr. David Lynch, one of the world’s greatest living artists, whose influence hovered over the entire festival. As an alumnus of the AFI Conservatory’s first class, Lynch had the honor of becoming the fest’s very first Guest Artistic Director. In addition to creating this year’s ominously optimistic festival poster, Lynch chose five films from the ‘50s and ‘60s which helped spark his own unique cinematic oeuvre.

“I picked these particular films because they are the ones that have inspired me the most. I think each is a masterpiece,” stated Lynch. “If people have already seen them, they are certainly worth being seen again. And if people haven’t seen them, here is an opportunity to see what I consider to be cinema at its best.”

One could not escape Lynch’s enthusiastic imprint throughout the week-long festival. His artwork for the fest – a brightly dressed clay figure hoisted above the threatening L.A. skyline by an inexplicable tendril – was ubiquitous. In addition, before each film screening a short video of Lynch extolling the virtues of the AFI was projected, a tribute which concluded with Lynch emphatically declaring to the camera, “I love AFI.”

One could not escape Lynch’s enthusiastic imprint throughout the week-long festival. His artwork for the fest – a brightly dressed clay figure hoisted above the threatening L.A. skyline by an inexplicable tendril – was ubiquitous. In addition, before each film screening a short video of Lynch extolling the virtues of the AFI was projected, a tribute which concluded with Lynch emphatically declaring to the camera, “I love AFI.”

The feeling was mutual, and the electricity inside Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre on the festival’s first Saturday was palpable. A beautiful print of Lynch’s first feature Eraserhead had just screened for the appreciative crowd. If not for the AFI’s early support, Lynch would likely have been unable to create this singular vision, the first of his many cinematic masterpieces. Thanks to the largesse (and patience) of AFI and the creative freedom their patronage allowed, he slowly nursed Eraserhead to life over the span of many years back in the early ‘70s. Because of AFI’s early generosity, Lynch’s career was launched, to the eternal gratitude of cinephiles the world over. So when Lynch was spied in the auditorium’s wings, even before being introduced, the audience erupted into spontaneous applause.

In the far-too-brief minutes that Lynch spoke to the rapt house, he answered a handful of Twitter-submitted questions (Most beautiful sound he’s heard? “I love the sound of wind. I also like the sound of silence.”) Having already filmed introductions to each of the five works he’d chosen for screening, he then went on to speak specifically of the film that was about to be projected, Billy Wilder’s Sunset Blvd. (one of Lynch’s all-time favorites).

“What Billy Wilder does so well is make a sense of place, a place and a world, that when you’re in it, it’s so complete, so beautiful,” Lynch rhapsodized.

And indeed it was, projected in all its black-and-white 35mm glory on the giant Egyptian screen. One can only hope though that Lynch wasn’t still in the house when an errant projectionist flicked a switch that superimposed the AFI logo over, of all places, the climactic scene where Norma Desmond descends the staircase for her final close-up. Bad cinematic karma, that.

Technical snafus aside, Lynch’s chosen quintet of audacious films were, for me, the highlight of the festival. His concise impressions of the films were delightful …

Sunset Blvd. –“I want to live in this world.”

Rear Window – “The best people, the best mood, the best setting for a murder mystery.”

Mon Oncle – “Exquisite, extreme, French ‘50s with the big heart and humor of Jacques Tati.”

Lolita – “Staggeringly great performances, direction, writing and mood.”

Hour of the Wolf – “Bergman’s surreal masterpiece conjures startling experiences.”

This final film, the one from the group that I’d previously not seen, was an outright revelation. Screening late Sunday night at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre to a relatively sparse crowd, Ingmar Bergman’s 1968 Hour of the Wolf was a surreal cinematic puzzle, all the more striking in that it was ostensibly based on the diaries of its two main characters (portrayed brilliantly by Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann). Rife with Bergman’s autobiographical touches, the film however seemed almost closer in style at times to Fellini’s La Dolce Vita or 8½. For that matter, Hour of the Wolf seemed a perfect bridge from those two seminal Fellini films to Eraserhead itself, as well as the other great psychological works Lynch would later create. As with many of Lynch’s dense films, it was only upon further reflection (and an impassioned late-night post-screening discussion), that I began to realize the bulk of the film is presented from the subjective, gradually shattering psyche of its main character. In contrast to Liv Ullmann’s direct-to-camera no-nonsense bookends that open and close the film, the veracity of events in the film’s central story grows ever suspect. As the film progresses, its style increasingly reflects the deteriorating state of its protagonist’s troubled mind, an obvious forerunner and inspiration for Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. And what a beautifully surreal psychodrama Bergman created in Hour of the Wolf, such an apt companion piece to Lynch’s own best work. More memorable yet was the privilege of seeing this film screened inside Hollywood’s most iconic cinema palace. And how perfect that both Hour of the Wolf and the Chinese Theatre are positioned (geographically and psychologically) somewhere just between Sunset Blvd. and Mulholland Dr.

This final film, the one from the group that I’d previously not seen, was an outright revelation. Screening late Sunday night at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre to a relatively sparse crowd, Ingmar Bergman’s 1968 Hour of the Wolf was a surreal cinematic puzzle, all the more striking in that it was ostensibly based on the diaries of its two main characters (portrayed brilliantly by Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann). Rife with Bergman’s autobiographical touches, the film however seemed almost closer in style at times to Fellini’s La Dolce Vita or 8½. For that matter, Hour of the Wolf seemed a perfect bridge from those two seminal Fellini films to Eraserhead itself, as well as the other great psychological works Lynch would later create. As with many of Lynch’s dense films, it was only upon further reflection (and an impassioned late-night post-screening discussion), that I began to realize the bulk of the film is presented from the subjective, gradually shattering psyche of its main character. In contrast to Liv Ullmann’s direct-to-camera no-nonsense bookends that open and close the film, the veracity of events in the film’s central story grows ever suspect. As the film progresses, its style increasingly reflects the deteriorating state of its protagonist’s troubled mind, an obvious forerunner and inspiration for Lynch’s Mulholland Dr. And what a beautifully surreal psychodrama Bergman created in Hour of the Wolf, such an apt companion piece to Lynch’s own best work. More memorable yet was the privilege of seeing this film screened inside Hollywood’s most iconic cinema palace. And how perfect that both Hour of the Wolf and the Chinese Theatre are positioned (geographically and psychologically) somewhere just between Sunset Blvd. and Mulholland Dr.

Kudos are deserved all around, but especially to AFI, not just for successfully presenting this diverse and exciting festival, but for initially nurturing (four decades ago?!) David Lynch’s singular vision and talent. And thank you, Mr. Lynch, for sharing, inspiring, and giving back so very much to the world of cinema.